“The Net interprets censorship as damage and routes around it.”

John Gilmore

I’m part of a small but enduring community of online weirdos centred around The Ricky Gervais Show, a comedy programme hosted by Ricky Gervais, Stephen Merchant, and producer Karl Pilkington on and off between 20011 and 2010. My own engagement with the show began in around 2007, and it remains my earliest comedy fandom. The show is now mostly forgotten, but it was, for a time, the number one podcast in the world, the first podcast adapted to television, and one of podcasting’s first true global successes.

Before it was a podcast, The Ricky Gervais Show was a lightweight frothy entertainment show heard from 11am–1pm every Saturday on tinpot London radio station Xfm. This radio incarnation is the show’s purest form, and the apotheosis of the trio’s humour. Long before Gervais became the world’s most tiresome boomer comic, writing 80 variations of the same “I identify as a chimpanzee” joke, he played against his own working class origins and skewered the banalities of British life in a way that was irreverent and edgy, to use a term that at the time wasn’t necessarily code for racist. The comic sensibility and timing he shared with the quick-witted Merchant, which would infuse all their later collaborative projects, is present from the very beginning. You can hear them improvise and develop embryonic versions of material they would later use in The Office‘s second series, Extras, and their stand-up comedy sets.

The real joy of the show, though, lies in hearing Gervais and Merchant discover, in real time, the true comedic genius occupying the third chair. Pilkington was originally brought on as an off-mic producer running the desk, but in short order Gervais and Merchant began integrating him into the show, and they discovered he possessed a bottomless well of bizarre stories of his Manchester upbringing and off-kiler views on the world. (Some highlights: the horse in the house; Auntie Nora’s ripped tennis ball; “man-moths”.)

The very fact that the Xfm Ricky Gervais Show still exists in listenable form today is largely thanks to the efforts of the show’s fandom, which is still surprisingly active. The community is mostly found on Discord and reddit, but it took off in the glory days of Web 2.0 on Pilkipedia.co.uk, a phpBB forum and wiki founded just as the podcast was taking off in 2006. (The “Pilkipedia” name is apt: it is with some irony that the show kept the name The Ricky Gervais Show, as it very quickly became clear that Pilkington was the real draw.) As fan communities, these forums are full of people who still listen to, discuss, and quote episodes of the show, now 20+ years after they were first broadcast. But as fans do, they also actively contribute to the fandom and the maintenance of the community via unpaid — and often highly skilled — labour. In the RSK community, as it is sometimes known, fans have collected and collated media clippings and trivia about the show and the people involved; they have painstakingly transcribed Gervais’s infamously punch-drunk gibberish; and they have written fan fiction. But by far the most lasting and impactful work of the RSK community has been in preserving and disseminating the show itself.

“Xfm 104.9. Five past one, of a Saturday…”

As a radio show broadcast live-to-air in the early 2000s, The Ricky Gervais Show was originally only able to be heard by those in range of Xfm’s London broadcast area. Listeners from outside London and those who missed it on its first broadcast had no way of listening, even after the podcast version of the show became a massive worldwide hit. This is, of course, one of the defining features of broadcast radio, but it’s also one of its key weaknesses.2 Luckily, fans of the show — two in particular, Richard Hare and Ian Pile — recorded many of the show’s original broadcasts to cassette tape, and they took it upon themselves to digitise the tapes, edit out songs and ads, and upload the files online to share with the community.

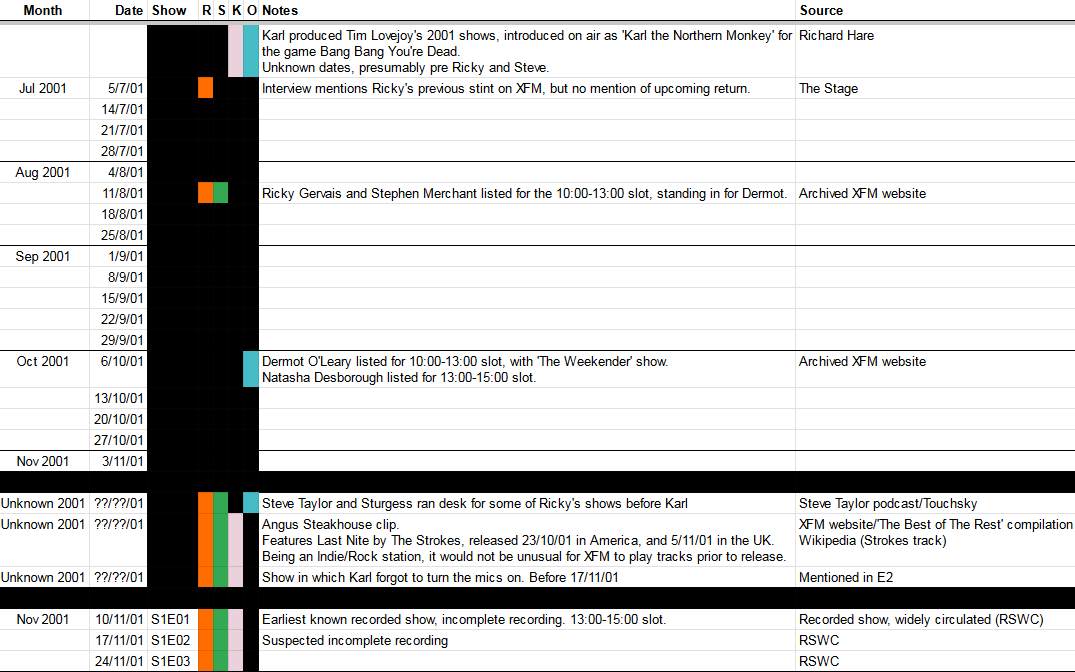

The extant corpus of The Ricky Gervais Show consists of this haphazard collection of mp3s, combining the recordings of Hare and Pile with the so-called “Jezoc tapes”, and a few other bits and bobs, for a total of about 100 episodes. The first mp3 in the collection is a recording of the broadcast from November 10, 2001, but the show actually first went to air several months earlier. How much earlier, nobody knows, as their return to Xfm was greeted with such indifference that not a single trade publication reported on it. No recordings of earlier episodes have ever surfaced, so the collection is still very much incomplete.

These files have been passed around successive file-sharing platforms as they have come and gone over the decades, first on LimeWire and Soulseek, then in MediaFire archives, and now on The Pirate Bay and other torrent websites. In terms of audio quality, the files in this collection have always been rough listening, reflective of the cirumstances in which they were recorded: straight off the radio onto consumer-grade cassette tape, hurriedly edited by amateurs and enthusiasts, and highly compressed for online distribution. In some files the audio is so hot as to be borderline unlistenable, while in others Pilkington is practically inaudible. Additionally, over the years unknown people have — for unknown reasons — sloppily edited the files down from their original form, losing several minutes of audio from some copies of the collection. As a result, there is no definitive version of the files that do exist.

But even acknowledging the inferior audio quality of the collection, if it weren’t for the efforts of the Pilkipedia community to record the show and make the files available to successive generations of listeners, this huge collection of comedy would have been lost forever. Xfm, for their part, have shown surprisingly little interest in making the show available to fans. The station made a cursory attempt to capitalise on their connection to RSK once their podcast became a massive success, but their offering was rather paltry: just a handful of highlight clips, edited and modified from the original. Over the years various fans have reached out to Xfm management to ask about the status of any back-up tapes, only to be continuously rebuffed.

Recent developments

In the 2010s, as many forums did, the Pilkipedia forum fell victim to the emergence of the walled-garden approach to internet community, typified by Facebook. The forum was gradually abandoned by users in favour of Facebook groups, while the burden of maintaining and keeping the forum spam-free became too great for admins, and the site went offline. There was a period of about five years where the RSK community was fractured and without a single point of congregation. But it did not entirely disband, and in the last year or so has seen a huge revival on Discord. This situation is not ideal, as Discord is yet another a walled garden, and therefore invisible to Google searches and the Wayback Machine. But, for the time being at least, it has led to a significant revivification of the community’s preservation efforts.

As I write this, a user going by the name of Rhondson is close to finishing a complete audio remaster of the Xfm Ricky Gervais Show. He has consolidated all known surviving recordings of the show from various sources, saved the versions that avoided being subjected to unexplained edits, picked the best sounding version, and is normalising and levelling the audio to be consistent across the series. He has posted draft versions of the files as he’s gone along, and the improvement is astounding.

Meanwhile, fans have been scouring the Wayback Machine and archives of newspapers and the Radio Times to piece together the show’s broadcast history, which is mostly lost to time. The date of the first Xfm broadcast has been triangulated as occurring in either August or September of 2001, with September 1, 2001 being the current front-runner.3 This is the sort of archival research and preservation work you hear about when a print of Metropolis with three seconds of previously unseen footage is discovered in an attic somewhere. But this archival work is not being done by boffins in white coats with information science degrees; it’s being done by untrained but passionate volunteers, on a Discord server, amidst a torrent of memes about Stephen Merchant’s eyes. This work would of course be so much easier if anyone involved at Xfm in the early 2000s had written a book (or even a social media post) about their experiences. But absent that, it’s up to the fans to put research, collect, and maintain this information themselves.

Fan-led preservation work of this kind is incredibly important, but still widely underestimated. It remains one of the best and most reliable ways our cultural history is preserved when rights holders and capitalists fail, which is often. We have long been promised a utopian digital future where the world’s content would be at our fingertips, unlimited and on-demand. Instead, we have fractured silos of content due to byzentine rights agreements, completed films being shelved or removed from streaming services for financial reasons, and content that depicts problematic characters being removed or edited without warning (even if those problematic characters are satirical).

Even physical media releases are not immune to this, as fans of MTV shows like The State, Beavis & Butthead and Daria are well aware (and outside of MTV there was Ed, and WKRP in Cincinnati, and The Wonder Years, and…). Licensing issues meant that DVD versions of those popular shows had almost all of their original music removed and replaced with generic approximations, completely butchering what fans enjoyed about the show in the first place. Beavis & Butthead is a particularly interesting case, as the show originally contained sequences in which the titular characters channel-surfed and “watched” music videos on MTV, commenting over the top in a manner not dissimilar to Mystery Science Theater 3000. Official releases of the show had all of these music video sequences cut out, leaving only the comparatively less interesting narrative storylines. The fan-created “King Turd Edition” collects the original versions of the show, taken from the best available source — which, unfortunately, is often a VHS recording of the original television broadcast — and restores the show to its original glory. Likewise, the Daria Restoration Project took video from the series’ official DVD releases and re-inserted songs that had been taken out, sourced either from the original broadcast version or (if there was no dialogue layered on top) by manually inserting the song.

With no financial incentive, Xfm/Radio X/Global Radio have no reason to make The Ricky Gervais Show available to the public. It is effectively orphaned media, and is in real danger of being lost forever once the rumoured DAT backups of the show held in long-term storage deteriorate, if they even exist to begin with. Whatever you think of Ricky Gervais’s embarrassing recent slide into reactionary politics, this would be a genuine loss for comedy history.

Piracy is necessary for the continued survival of our culture

It goes without saying, of course, that RSK fans preserving the show is illegal, as the community has no right to distribute these copyright works on the internet. But this is a case — one of many — where copyright law and the so-called free market have failed. Copyright laws were originally written to preserve the artist’s ability to control the distribution and monetisation of their own work. Copyright was supposed to encourage the spread of culture and art by ensuring any profit generated by an artwork went to the artist whose labour produced it. The usual argument in favour of copyright is that this situation benefits not just artists but also the public at large, as copyright holders are encouraged to increase the availability and access to their works. But of course this is not the world we live in. We live in a neoliberal hellscape in which gargantuan media conglomerates slurp up intellectual property and sit on it, with no intention of ever letting it see the light of day, like dragons hoarding piles of gold coins.

What are we to do in such a situation, when a rights holder has made clear their intention not to exploit their exclusive right to capitalise a copyright work? There are countless historically significant radio programmes, television shows, and other media that simply cannot be enjoyed by modern audiences, because they represent too small a potential profit for the copyright holder to bother. But, surely, the preservation of our cultural history cannot, and must not, depend on its profitability.4 Should there be a carve-out in copyright law to allow the preservation and distribution of quasi-orphaned works such as these? Of course, I don’t expect anyone will ever be prosecuted for downloading episodes of The Ricky Gervais Show, or making them available on a new torrent tracker. But they could be, and that is a problem. There must be more we can do at a policy level to encourage the preservation and distribution of important works of our cultural history.

For now, in cases where rights holders are unwilling to take on the task, fandoms and communities must pick up the slack.

Footnotes

- There was an earlier incarnation of The Ricky Gervais Show that went to air on Xfm in 1998, featuring Gervais and Merchant but no Pilkington. There is debate in the fandom about where this series sits in the show’s canon, leading to its unofficial designation as “Series 0”.

- “Ephemerality has been a major problem across radio’s more than a century long history: as a live broadcast medium, much radio programming was never recorded.” — Andrew J. Bottomley, “Podcast Archeology: Researching Proto-Podcasts and Early Born-Digital Audio Formats” in J.W. Morris & E. Hoyt (eds), Saving New Sounds: Podcast Preservation and Historiography, Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, pp. 29–50.

- As a scholar interested in the intersection of media and culture, I am desperate to get my hands on the broadcast from September 15, 2001.

- I was so pleased to read Senses of Cinema‘s excellent recent issue on cinema and piracy, which dealt with the issue with considerable nuance.